The following land acknowledgment statement has been prepared by the Pennsylvania Youth Congress in 2020. It is the custom of PYC to have a land acknowledgement statement delivered at the start of formal conferences and programs. We invite you to share this statement, with or without attribution.

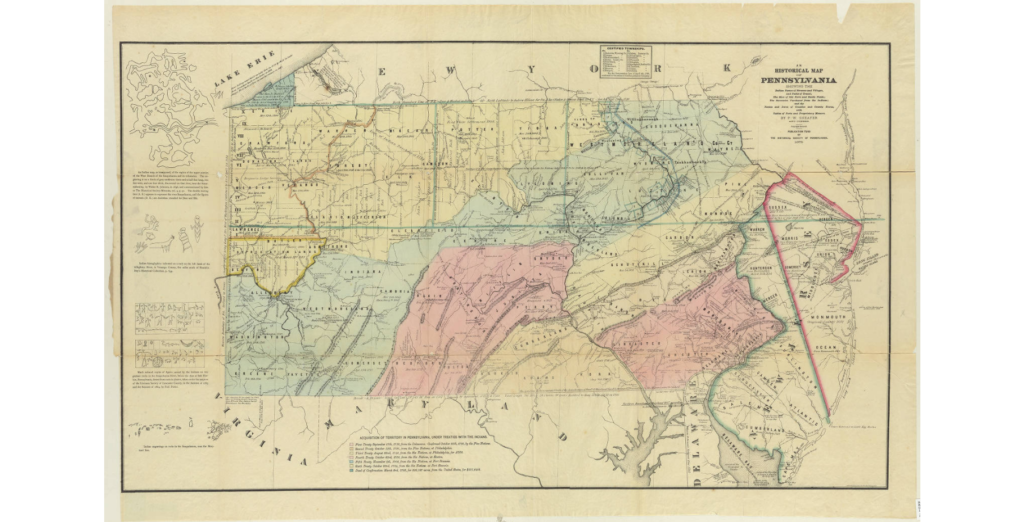

We recognize and acknowledge Pennsylvania as being the land of the Erielhonan (Erie), Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Lenni-Lenape, Shawnee, Susquehannock, and Tuscarora nations, and the Honniasont, Saluda, Saponi, Tutelo, and Wenrohronon tribes. We pay respect to the Native peoples of Pennsylvania past, present, and future and their continuing presence in their homeland and throughout their diasporas.

The experience of Native peoples with European colonists in present-day Pennsylvania was not entirely peaceful as is often taught today. We hold ourselves accountable to understanding and bringing forward the real history of Native peoples whose land Pennsylvania now occupies. Native peoples who lived in Pennsylvania for thousands of years encountered colonial deceit, disease, and warfare, with only a few nations and tribes having living descendants today.

The Lenni-Lenape, also known as the Lenape or Delaware Indians, are the people who, during the 1680s, conferred with William Penn to facilitate the founding of the colony of Pennsylvania. Their descendants today include the Delaware Tribe and Delaware Nation of Oklahoma; the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape, Ramapough Lenape, and Powhatan Renape of New Jersey; and the Munsee Delaware of Ontario.

The Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois, is the confederacy of the Six Nations. These nations include the Cayuga, Mohawk, Seneca, and Tuscarora whose home over time included portions of western, central, and eastern Pennsylvania. Today their descendants largely live in North Carolina, New York, Ontario, and beyond.

The Erielhonan lived along the southern shores of Lake Erie in northwestern Pennsylvania. Erie is short for “Erielhonan” which means ‘long tail’. The home of the Wenrohronon tribe was across western New York and small portions of northern Pennsylvania. Along with the Susquehannock and other Native peoples, they were collectively known as the Atiwandaronk, or ‘they who understand the language’, by the Huron. In the mid-17th century the Erie, Wenrohronon, and Susquehannahock were overwhelmed by the Haudenosaunee, with only the Susquehannock surviving as an independent people.

The Susquehannock were an Iroquois-speaking people whose home extended along the present-day Susquehanna River and its tributaries. Also known as the Conestoga, the Susequhannock people reached their height in the mid-17th century as a confederacy of several dozen tribes from the start of the Susquehanna River in southern New York, throughout central and eastern Pennsylvania, and into greater present-day Maryland. The Susquehannahock were later decimated by disease and conflicts with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois), ultimately resulting in many Susquehannock migrating west and being absorbed into other tribes. Only a few hundred Susquehannock remained in the Susquehanna Valley into the mid-18th century. In 1763, a massacre of 20 Susquehannock in Conestoga, south of Lancaster, took place by colonial vigilantes involved seeking retribution against Native peoples for the Potomac Wars. The surviving few Susquehannock lived the rest of their lives near present-day Manheim in Lancaster County.

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking people who historically migrated across the mid-Atlantic, Midwest, and Deep South. Their home included portions of Pennsylvania over time. Shawnee people live in communities today throughout the United States, prominently in Oklahoma and Alabama.

Several tribes have called Pennsylvania home over time, including the Honniasont, Saluda, Saponi, Tutelo peoples. There is limited documentation on the history of these tribes in Pennsylvania.

For nearly 40 years, Native children from across the United States were forced to attend the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in central Pennsylvania to explicitly remove all of their Native connections, cultural identities, spoken languages, spirituality, and even their names. Used as a model for similar institutions across America, the stated goal of the school by its founder was to “kill the Indian, save the man” in line with cultural genocide. From 1879 until the school closed in 1918, over 10,000 Native children from more than 140 tribes were subjected to this unconscionable experience, within Pennsylvania. Nearly 200 children died while in custody at this facility. Based in Conestoga, PA, the Carlisle Indian School Project is a nonprofit organization that continues to document the history of this institution.

Native terms are the names of many cities, townships, counties, and boroughs in Pennsylvania. Additionally, Native words are the monikers of numerous government-defined natural features and local institutions. Opportunities to meaningfully honor the legacy of Native peoples should be welcomed in context, and in partnership behind Native individuals and communities. However, it is not acceptable for terms or references on Native peoples to be weaponized as racist props for athletic team mascots or other institutions. It is our responsibility to ensure anti-Native racism is never sanctioned or celebrated.

There are no federal or state recognized tribes in Pennsylvania because of centuries of violence, genocide, disease, and forced removal. However, Native people live throughout the commonwealth today. The history of the Native peoples whose land is now occupied as Pennsylvania and those who have later come to Pennsylvania should be honored every single day.

A land acknowledgement is not enough. We must commit our solidarity with the sovereignty and self-determination of all Native peoples. Social justice means decolonization. This land acknowledgement is an opening for us all to understand the role each of us have in supporting Native peoples right now.

As a living statement, this Native Land Acknowledgment may be periodically updated.